Un roman de revanche sociale

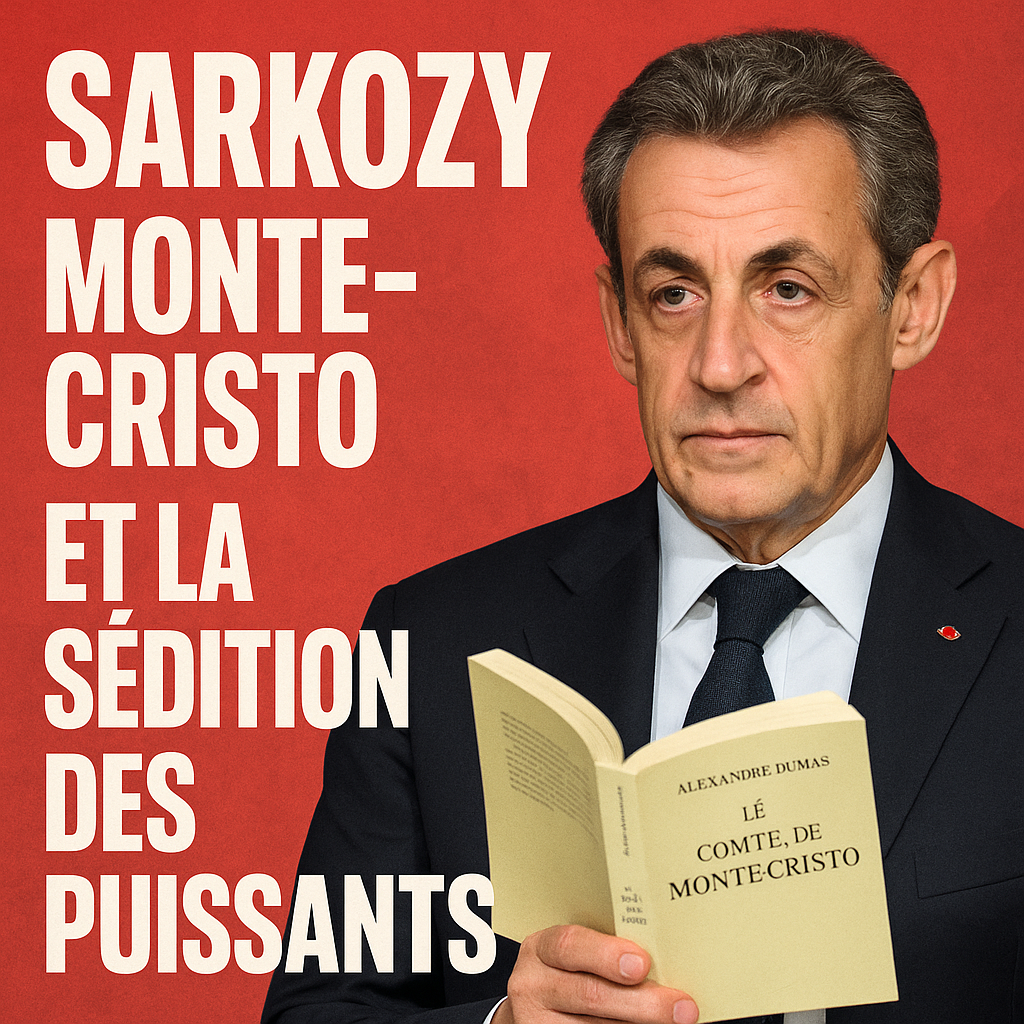

Quand Nicolas Sarkozy se rend en prison avec Le Comte de Monte-Cristo dans son sac, la symbolique n’échappe à personne. Edmond Dantès, injustement condamné, revient pour solder ses comptes avec une société hypocrite. Mais la comparaison s’arrête là. Le retour de Sarkozy n’a rien du héros populaire. Il ne paie pas l’injustice des puissants, il en incarne la revanche.

Car si le président déchu est aujourd’hui un condamné pour association de malfaiteurs, il reste un homme d’affaires prospère, administrateur ou partenaire de groupes comme Lagardère, Accor ou Bolloré. Le monde économique, lui, ne l’a pas excommunié. Les conseils d’administration lui gardent sa chaise, les plateaux de télévision ses micros, et les dîners de Neuilly son couvert.

L’indulgence des puissants

Ce n’est pas seulement le réseau Bolloré qui continue de l’entourer. C’est une classe tout entière, celle qui s’estime au-dessus des verdicts. Depuis des semaines, les éditorialistes de droite hurlent au “despotisme judiciaire”. Gérald Darmanin a cru bon d’annoncer qu’il lui rendrait visite en détention, et le président Macron a reçu l’ex-chef d’État “sur un plan humain”.

Ce “plan humain” vaut sans doute plus pour certains que pour d’autres. Car il n’est pas certain que le même élan de compassion s’exprime lorsqu’un salarié est licencié pour avoir récupéré des denrées périmées, ou lorsqu’un sans-abri écope d’une peine pour vol alimentaire. La justice est humaine, paraît-il, mais certains sont plus humains que d’autres.

L’aristocratie d’impunité

L’affaire Sarkozy dépasse de loin le cas individuel. Elle révèle ce que l’on pourrait appeler une sédition feutrée des élites — une rébellion non pas contre le pouvoir, mais contre le principe même de la loi commune. Dans une démocratie fatiguée, où le pouvoir judiciaire tente encore de maintenir un reste d’égalité, la condamnation d’un ancien président provoque l’indignation… non des opprimés, mais de ses pairs.

Cette colère n’est pas un accident : elle traduit la résistance d’un système où les frontières entre politique, affaires et médias se sont dissoutes. Les grands groupes de presse appartenant aux amis de l’ancien président (Bolloré, Arnault, Lagardère) orchestrent désormais la dramaturgie de l’injustice, transforment une condamnation pénale en martyr politique et préparent le terrain à un discours dangereux : celui de la défiance envers la justice au nom du pouvoir des puissants.

La contagion mondiale du privilège

Ce phénomène n’est pas propre à la France.

Aux États-Unis, Donald Trump a fait de ses inculpations un programme électoral ; en Italie, Silvio Berlusconi en avait fait un art de vivre ; en Israël, Benjamin Netanyahou a modelé les lois à sa survie politique. Partout, les élites économiques et politiques réécrivent la morale publique selon leur code d’honneur.

La démocratie n’est plus trahie par les coups d’État militaires, mais par une lente érosion du sens commun de la justice — un séparatisme de classe qui réclame pour lui l’impunité au nom de “l’efficacité”, du “talent”, ou de “l’expérience”.

La revanche de Dantès n’aura pas lieu

Le parallèle avec Dumas se retourne donc comme un gant. Là où le romancier faisait de l’injustice un moteur de révolte, notre époque en fait un privilège défiscalisé.

Sarkozy ne revient pas pour renverser les puissants, il revient parmi eux. Son “retour du bagne” n’est pas une rédemption, mais une reconstitution : celle d’un système où la justice ne vaut que pour ceux qui n’ont pas les moyens de s’en défendre.

Conclusion : une fracture démocratique

L’affaire n’est pas qu’un scandale moral. Elle met à nu un déséquilibre structurel entre droit et pouvoir, aggravé par une concentration médiatique sans précédent.

Quand les gouvernants prennent la défense des condamnés puissants au nom de “l’humanité”, mais imposent la rigueur et la morale punitive aux plus modestes, c’est tout l’édifice républicain qui vacille.

Ce n’est plus la République qui protège la justice, mais la justice qui tente, seule, de protéger la République.

Sarkozy, Monte Cristo, and the Revolt of the Powerful

A novel of social revenge

When Nicolas Sarkozy walked into prison carrying The Count of Monte Cristo in his bag, the symbolism was hard to miss. Edmond Dantès, the wronged man who defies fate and returns to settle his scores—an image of resilience and redemption.

But here, the comparison ends. Sarkozy is no Dantès. His return is not the triumph of justice over oppression; it’s the resilience of privilege under the disguise of misfortune.

While the former French president is now serving time for criminal association, he remains a well-connected businessman, board member or partner of groups such as Lagardère, Accor, and Bolloré. The corporate world hasn’t turned its back on him. His seat on the boards remains reserved, the microphones of television studios stay open, and the grand Parisian salons have kept his place at the table.

The indulgence of the elite

It’s not only Vincent Bolloré and the tight network of media oligarchs who protect him. It’s a whole caste—one that sees itself as above the law. For weeks, conservative and far-right columnists have been hammering the same message: that Sarkozy is a victim of “politicized judges,” that France is falling into “judicial despotism.”

Justice, they say, has become tyrannical—at least when it dares to reach the powerful.

Even the government seems to echo this sentiment. Justice Minister Gérald Darmanin publicly declared he would visit Sarkozy in prison. President Emmanuel Macron received him at the Élysée before his incarceration, explaining it was “human” to do so.

Human, perhaps—but not equally for everyone. One wonders where this compassion hides when an ordinary worker is fired for taking expired food from a dumpster. Some forms of “humanity” are clearly more selective than others.

The aristocracy of impunity

This episode goes far beyond the fate of a single man. It signals what might be called a rebellion of the elites—a quiet secession of the rich and powerful from the rule of law.

The outrage over Sarkozy’s conviction isn’t an anomaly; it’s a symptom. It reflects a deeper refusal by the ruling class to submit to the same justice as ordinary citizens.

France’s most influential media outlets, owned by the billionaire friends of the former president—Bolloré, Arnault, Lagardère—now act as both shield and megaphone. They manufacture empathy for the convicted and outrage at the courts. In this narrative, the judiciary becomes the enemy, and the guilty become martyrs.

What we are witnessing is the normalization of privilege as virtue—and of accountability as persecution.

A global epidemic of privilege

This is not uniquely French.

In the United States, Donald Trump turned his indictments into a campaign platform. In Italy, Silvio Berlusconi made his trials a lifestyle. In Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu rewrote the law to protect himself from it.

Everywhere, elites are rewriting the moral code to justify impunity. The new populism of the wealthy demands the right to break the law in the name of “efficiency,” “talent,” or “leadership.”

It’s not the generals who threaten democracy today—it’s the billionaires and former presidents who defy its rules with a smile and a press team.

The revenge of Dantès will not come

Sarkozy’s Monte Cristo moment is pure theatre.

Where Dumas turned injustice into rebellion, our time turns it into branding.

Sarkozy isn’t returning to punish the powerful—he’s coming back among them. His “return from exile” isn’t a redemption story; it’s the continuation of a system that forgives everything to those who own everything.

A fracture at the heart of democracy

This case is not just a scandal; it’s a revelation. It exposes a structural imbalance between law and power, amplified by media concentration and political cynicism.

When leaders defend convicted elites in the name of “humanity” but impose moral discipline on the poor, democracy itself begins to rot.

What remains is not the Republic protecting justice—but justice, lonely and besieged, protecting what’s left of the Republic.